Security Council: Securing peace in the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh

- Aidyn Despiau-Vazquez - Reporter

- Dec 11, 2020

- 4 min read

The Caucasus mountain region has been of great geopolitical significance to South-East Europe. It’s home to a vast supply of oil and natural gas and serves as a shatter belt between the powers of Russia and Turkey.

Yet shatter belts are further characterized as being under constant political stress resulting from their status of fragmentation. Two states located in the Caucasus are Armenia and Azerbaijan, both of which were a part of the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. As with many of the nations once a part of the USSR, ethnic tensions were—and continue to be—prevalent between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. The two nations have ensured the Caucasus lives up to its fragmented status with their persistent, on-again-off-again dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

So what’s the deal with Nagorno-Karabakh? The region is, by majority, ethnically Armenian, with over ninety-nine per cent of the population being a part of the Christian faith. Ninety-eight per cent of such belongs to the Armenian Apostolic Church. Yet when the Soviet Union was formed in the 1920s, the region was put under Azerbaijani control. Azerbaijan’s religious composition has consistently been predominantly Muslim, and current statistics cite ninety-four to ninety-six per cent of Azerbaijan’s population to be Muslim.

While the population and authorities of Karabakh were already dabbling in separatist conversation during the 1980s, tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan remained relatively peaceful. However, the decline of the Soviet Union roused these tensions and gave the enclave its chance to give self-governance a whirl. By 1988, Armenians and Azerbaijanis were accusing each other of threatening ethnic cleansing and pogroms against the other, Karabakh regional authorities officially voted to unify with Armenia, and the First Nagorno-Karabakh War began.

Once both nations became independent in 1992, the war reached its climax. As many as 230,000 Armenians from Azerbaijan and 800,000 Azerbaijanis from Armenia and Karabakh were displaced. Essentially, Armenia and Karabakh were cleansed of Azerbaijanis. Likewise, the Armenian population of Azerbaijan became almost nonexistent. The death toll of the war between 1988 and 1994 is estimated to have between 5,000 and “tens of thousands”, according to BBC.

Despite Armenia having control of most of the enclave, the 1994 Russian-brokered ceasefire called for Karabakh to remain in Azerbaijan’s possession. Nonetheless, the region continues to be a self-declared republic and remains to be ruled by separatist ethnic Armenians backed by the Armenian government. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group serves as the regulator for peace-talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

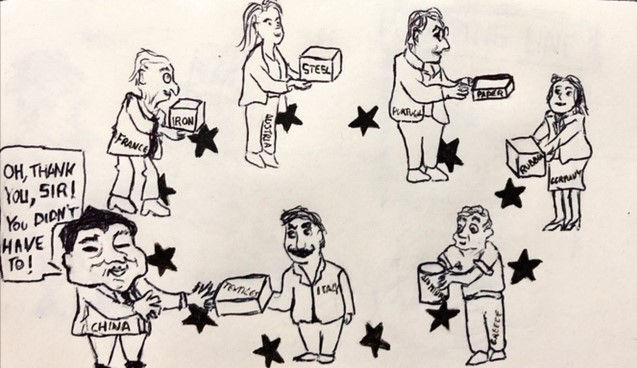

The current issue is that the OSCE and the rest of the global community have seemingly failed to carry out the mission of facilitating peace between the two nations. Since 1994, several clashes resulting in numerous Armenian and Azerbaijani fatalities alike have surfaced. The culmination of these clashes seems to be the beginning of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War on the 27th of September this year. The OSCE’s presence in the enclave seems not to matter to nations such as Turkey, who, during both wars, increased tensions. During the First Karabakh War, Turkey closed its borders with Armenia in support of Azerbaijan, a fellow Turkic nation. This time around, Turkey has been providing substantial military support to Azerbaijan. This was in response to yet another breakout of conflict on the international Armenia-Azerbaijan border in July of 2020. The political cartoon above illustrates the dynamic between the OSCE and Turkey in the midst of the ostensibly indefinite Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

After 44 days of fighting, the latest conflict came to an end after yet another Russian-brokered peace deal. The Guardian estimates that “thousands have been killed and more than 100,000 displaced in the worst fighting since the early 1990s”. The peace deal leaves Karabakh under the control of Azerbaijan and free of Armenian troops. However, attempted mediation comes in the form of a “peace corridor” in which Armenia is linked to territory in Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia currently monitors the peace agreement with the aid of 2000 Russian peacekeepers.

The question now is whether or not this détente will last. Judging by the history of Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, tensions are far from being relieved. Little to no distinction can be made between the two short-lived truces of 1994 and 2020. Azerbaijan has remained in control of the enclave since the 1920s, and the ethnic Armenians of Karabakh show no sign of letting up on fulfilling their cultural identity. In fact, cleansing of the regions since the First Karabakh War may only serve to rekindle the separatist movement with a stronger fire now that ethnic Azerbaijanis are void from the region. Conflict is even less likely to be refused by either side considering the minimal interference provided by the OSCE and other organizations. Turkey’s unwavering support of its Turkic ally would only heighten Azerbaijani confidence in prevailing in any conflict over Karabakh against Armenia.

Another question to ask is whether or not Russia’s close relations with Armenia will cause a ripple effect of conflict outside the Caucasus. As a persistent mediator between Armenia and Azerbaijan, this seems unlikely. Moscow recognizes the value of the geographical position of the two nations and has therefore pursued a policy of neutrality concerning conflict in Karabakh.

However, if the current peace is disrupted and tensions escalate once again, the presence of Russian troops in the region may set the stage for the expansion of the Russia-Turkey proxy conflict. The Wall Street Journal claims Russian troops have failed to establish a sense of security among Armenians, and distrust is prevalent. In addition to this, ties between Russia and Azerbaijan are extremely weak. When taking this in consideration, it seems Russia is half-hearted in its endeavors to ensure peace and further lacks any true relations with Azerbaijan strong enough to continue ignoring the increasing Turkish forces within its borders. The prospect of the proxy war growing is likely, the 2019—2020 Western Libya Campaign shows that easily enough. However, whether or not significant intensification will come from tensions in Karabakh is difficult to say.

What is probably more evident is that if unsubstantial change is made within the terms of mediation between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the current establishment of peace between them is highly unlikely to continue for a good period of time. The Security Council will be discussing ways to reinforce the current peace agreement as well as possible solutions to the conflict as a whole.

Comments