Council of the European Union: Evaluation of EU Relations with China

- Lia Magalhães - Reporter and Cartoonist

- Dec 11, 2020

- 2 min read

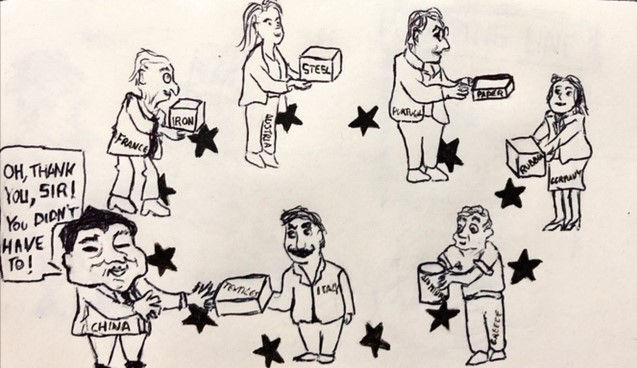

The European Union and China are two of the biggest traders in the world. However, while China relies primarily on the EU, it has now gone to second place. This means stricter behavior will be expected by the EU, who begins to stress the ideas of fair trade, respect for intellectual property rights, and its obligations as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). When China joined the WTO in 2001 it agreed to reform and liberalise important parts of its economy, and though China has made some progress, problems remain.

Negotiations now aim to improve transparency, licensing and authorisation procedures, as well as to provide a high and balanced level of protection for investors and investments. These measures showcase the lack of reciprocity in Sino-European economic relationship, a fact that the EU is becoming more aware of each day. Concerns mount within the EU about China’s assertive approach abroad as well as its breaches of international legal commitments, and the massive violations of human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

This skepticism has come to escalate further with the current pandemic as concerns lie on Beijing’s intentions. European countries have already started considering the reduction of dependency on China for supplies of critical goods, substantiated also on concerns about the future of the relationship in a rapidly shifting geopolitical environment marked by China-US growing rivalry; the EU intends to maintain strong relationships with its number one partner (not China).

As suggested by data from the European Council on Foreign Relations’ EU Coalition Explorer, member states now view China pragmatically as a partner, but also almost everywhere simultaneously as a rival. With very few exceptions, members agree that the EU needs to restrict Chinese investments in strategic sectors, underlining their growing wariness of overdependence and exposure to the political and economic risks emanating from China.

Member states are increasingly dissatisfied with China’s unwillingness to reciprocate the openness of the EU market. Most of them – not least Bulgaria, Poland, and Italy – are keenly aware that they still receive relatively little Chinese investment, despite signing cooperation agreements with China or joining groupings such as the 17+1, and are determined to gain greater economic benefits from the Chinese economy without increasing their dependency on China, particularly given that the country’s economy is recovering from the pandemic faster than Europe’s.

Will this be the end of Sino-EU partnership? Or just a shift on reliance from China to the USA?

Comments